BACK TO STORYTELLING

December 4, 2022

Next year marks the 10th anniversary of my first published book, His Life Abiding. Even as I write this, I can hardly believe that ten years have elapsed, especially since the book was almost two decades in the making.

If you’ve read this paranormal mystery, you know the plot revolves around the capture, imprisonment and subsequent murder of a German POW named Ehren Tschantz during World War II. In the author’s note at the end of the book, I wrote that Tschantz’s story was based on the U.S. military’s practice of using captured Germans with anti-Nazi feelings as “stool pigeons” to extract information from other prisoners. What I didn’t reveal was my family's weird connection to the actual murder case that inspired His Life Abiding.

To explain this, I need to go back to 1998 when The History Channel premiered a documentary entitled America’s Last Mass Execution. Based on the book Martial Justice: America’s Last Mass Execution by Richard Whittingham, the film chronicled in part the capture and murder of a German prisoner of war named Werner Drechsler.

And this is where everything started...

December 4, 2022

Next year marks the 10th anniversary of my first published book, His Life Abiding. Even as I write this, I can hardly believe that ten years have elapsed, especially since the book was almost two decades in the making.

If you’ve read this paranormal mystery, you know the plot revolves around the capture, imprisonment and subsequent murder of a German POW named Ehren Tschantz during World War II. In the author’s note at the end of the book, I wrote that Tschantz’s story was based on the U.S. military’s practice of using captured Germans with anti-Nazi feelings as “stool pigeons” to extract information from other prisoners. What I didn’t reveal was my family's weird connection to the actual murder case that inspired His Life Abiding.

To explain this, I need to go back to 1998 when The History Channel premiered a documentary entitled America’s Last Mass Execution. Based on the book Martial Justice: America’s Last Mass Execution by Richard Whittingham, the film chronicled in part the capture and murder of a German prisoner of war named Werner Drechsler.

And this is where everything started...

U-118 under attack by American warplanes. (US Navy photo)

U-118 under attack by American warplanes. (US Navy photo)

WHO WAS WERNER DRECHSLER?

Born on January 17, 1923, Werner Drechsler grew up in the picturesque town of Chemnitz in eastern Germany, about thirty miles from the Czech Republic. According to Wittingham’s book, Drechsler was an intelligent child with a somewhat devilish personality and an aptitude for art and history. After the Nazis came to power, Drechsler gave up his academic studies to attend a mechanical trade school due to the government’s emphasis on “practical skills” valuable to the country’s military mobilization.

In 1941, with the Second World War raging, Drechsler volunteered for the elite but highly hazardous U-boat service. He was sent to the port city of Kiel for advanced submarine training and assigned to U-118 under Captain Werner Czygan.

If Drechsler entered the U-boat service due to patriotic fervor, he had severe doubts about his country’s political leadership by February 1943. Although he hid his feelings from his crewmates, Drechsler increasingly began to think of Adolf Hitler as a personal enemy. This change of heart may have been partly due to his father’s imprisonment for his anti-Nazi views, and partly due to the death and destruction he’d witnessed over the intervening years.

On June 12, 1943, Drechsler’s life would take a momentous turn, and he’d find himself able exact his revenge against the Nazis. On that day, American warplanes from the U.S.S. Bogue attacked U-118 while it was surfaced. Captain Cyzgan ordered the crew to abandon ship. Although Drechsler was wounded during the attack, he threw himself into the water before the U-boat exploded. He was only one of sixteen survivors.

Born on January 17, 1923, Werner Drechsler grew up in the picturesque town of Chemnitz in eastern Germany, about thirty miles from the Czech Republic. According to Wittingham’s book, Drechsler was an intelligent child with a somewhat devilish personality and an aptitude for art and history. After the Nazis came to power, Drechsler gave up his academic studies to attend a mechanical trade school due to the government’s emphasis on “practical skills” valuable to the country’s military mobilization.

In 1941, with the Second World War raging, Drechsler volunteered for the elite but highly hazardous U-boat service. He was sent to the port city of Kiel for advanced submarine training and assigned to U-118 under Captain Werner Czygan.

If Drechsler entered the U-boat service due to patriotic fervor, he had severe doubts about his country’s political leadership by February 1943. Although he hid his feelings from his crewmates, Drechsler increasingly began to think of Adolf Hitler as a personal enemy. This change of heart may have been partly due to his father’s imprisonment for his anti-Nazi views, and partly due to the death and destruction he’d witnessed over the intervening years.

On June 12, 1943, Drechsler’s life would take a momentous turn, and he’d find himself able exact his revenge against the Nazis. On that day, American warplanes from the U.S.S. Bogue attacked U-118 while it was surfaced. Captain Cyzgan ordered the crew to abandon ship. Although Drechsler was wounded during the attack, he threw himself into the water before the U-boat exploded. He was only one of sixteen survivors.

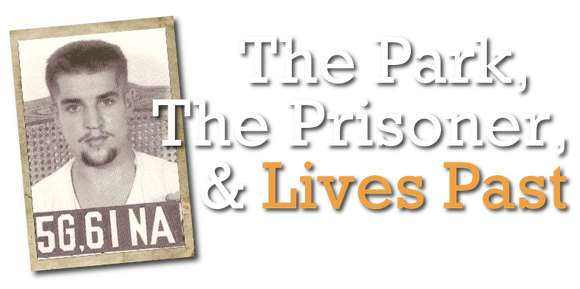

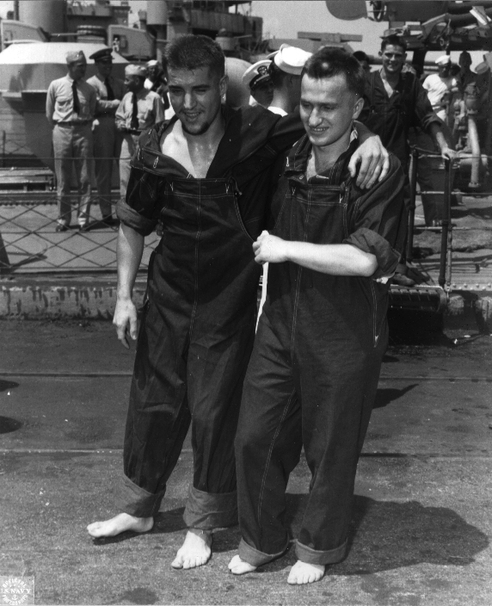

An injured Drechsler arrives in the U.S. as a POW. (US Navy photo)

An injured Drechsler arrives in the U.S. as a POW. (US Navy photo)

After being rescued at sea, Drechsler ended up in a naval hospital in Norfolk, Virginia, and was later transferred to Fort Meade, Maryland, for interrogation. Even before arriving at Fort Meade, naval personnel knew that Drechsler was ardently anti-Nazi. Drechsler was so anxious to help the Americans that he provided nearly eighty pages of notes, including everything from the position of official brothels in France to technical information about U-boats. He was given the codename “Limmer” and placed within bugged cells at the Fort Meade detention center to get uncooperative prisoners to talk. He was very good at this.

Because of his status as a “stool pigeon”, Navy documents noted that Drechsler should “never be sent to a prisoner of war camp where other German naval prisoners of war were held.” Navy officials even promised the twenty-two-year-old assistance after the end of the war, including possible asylum within the United States.

However, Drechsler’s usefulness faded as the Allies became increasingly successful at destroying the U-boat threat. In March 1944, he was transferred to the Army POW Camp at Papago Park, outside Phoenix, Arizona. This decision was never explained, although it violated the Navy’s instructions regarding Drechsler’s safety.

News of Drechsler’s arrival spread quickly among the German POWs, and many submariners who he had interrogated at Ft. Meade hurried off to see if he was, in fact, the infamous “Limmer.” Although there was never a consensus on his identity, a small group of prisoners decided he had to die.

At 8:30 p.m., seven men attacked Drechsler in his barracks. Amazingly, he fought them off, and a passing military jeep caused the conspirators to scatter. Although the military police heard Drechsler’s cries for help, they didn’t respond. Fifteen minutes later, he was attacked a second time, dragged by his hair to the nearby shower room, and hung from the rafters using an electrical cord. He died there, less than six hours after arriving.

Because of his status as a “stool pigeon”, Navy documents noted that Drechsler should “never be sent to a prisoner of war camp where other German naval prisoners of war were held.” Navy officials even promised the twenty-two-year-old assistance after the end of the war, including possible asylum within the United States.

However, Drechsler’s usefulness faded as the Allies became increasingly successful at destroying the U-boat threat. In March 1944, he was transferred to the Army POW Camp at Papago Park, outside Phoenix, Arizona. This decision was never explained, although it violated the Navy’s instructions regarding Drechsler’s safety.

News of Drechsler’s arrival spread quickly among the German POWs, and many submariners who he had interrogated at Ft. Meade hurried off to see if he was, in fact, the infamous “Limmer.” Although there was never a consensus on his identity, a small group of prisoners decided he had to die.

At 8:30 p.m., seven men attacked Drechsler in his barracks. Amazingly, he fought them off, and a passing military jeep caused the conspirators to scatter. Although the military police heard Drechsler’s cries for help, they didn’t respond. Fifteen minutes later, he was attacked a second time, dragged by his hair to the nearby shower room, and hung from the rafters using an electrical cord. He died there, less than six hours after arriving.

Drechsler (second from the left) with some of the other survivors of U-118. (US Navy photo)

Drechsler (second from the left) with some of the other survivors of U-118. (US Navy photo)

MY FAMILY CONNECTION TO THE DRECHSLER MURDER

After showing the History Channel documentary to my father, I was astounded when he told me that his childhood friend, the late Raimund “Ray” Radeke, was a military police officer stationed at Papago Park. In all the years they had known each other, my father had never discussed Ray’s experiences at the POW camp but promised to call him about it as soon as possible.

In the following months, I exchanged numerous phone calls and letters with Ray. Not only was Ray aware of Drechsler’s murder, he claimed that he helped cut down the body from the shower room rafters, and his eyewitness account was haunting.

“He died by having the other men beat his testicles with GI-issued boots,” he told me. “It had to be the worst death any man could suffer.”

Following his hanging, or perhaps even while Drechsler was still alive, Ray said the murderers “stripped the skin off his face and fingers so no one could identify him.” I couldn’t find this detail mentioned in any other source so it may have been Ray’s misinterpretation of the gruesome spectacle he encountered that March morning. However, but the coroner’s report noted extensive damage to the face and fingers and evidence that the body was repeatedly beaten even after death, probably by the hundreds of German POWs who paraded by it as it dangled from the shower room rafters.

The violence of the crime demonstrated an almost pathological hatred of Drechsler. In the investigation that followed, it was determined that his killers were die-hard Nazis, so their rage toward Drechsler went far beyond simple patriotism.

After showing the History Channel documentary to my father, I was astounded when he told me that his childhood friend, the late Raimund “Ray” Radeke, was a military police officer stationed at Papago Park. In all the years they had known each other, my father had never discussed Ray’s experiences at the POW camp but promised to call him about it as soon as possible.

In the following months, I exchanged numerous phone calls and letters with Ray. Not only was Ray aware of Drechsler’s murder, he claimed that he helped cut down the body from the shower room rafters, and his eyewitness account was haunting.

“He died by having the other men beat his testicles with GI-issued boots,” he told me. “It had to be the worst death any man could suffer.”

Following his hanging, or perhaps even while Drechsler was still alive, Ray said the murderers “stripped the skin off his face and fingers so no one could identify him.” I couldn’t find this detail mentioned in any other source so it may have been Ray’s misinterpretation of the gruesome spectacle he encountered that March morning. However, but the coroner’s report noted extensive damage to the face and fingers and evidence that the body was repeatedly beaten even after death, probably by the hundreds of German POWs who paraded by it as it dangled from the shower room rafters.

The violence of the crime demonstrated an almost pathological hatred of Drechsler. In the investigation that followed, it was determined that his killers were die-hard Nazis, so their rage toward Drechsler went far beyond simple patriotism.

SEARCHING FOR DRECHSLER'S MURDER SITE:

By January 1999, my father and I were deeply invested in Drechsler’s story and drove from Tucson to Tempe to find what remained of the Papago Park site. Half a century had elapsed, and most of the area was buried beneath modern construction. Fortunately, there were two prominent landmarks still in existence. The first was the Arizona Crosscut Canal which ran up the eastern perimeter of the POW camp. The second was Barnes Butte, a lumpy outcrop of granite to the west that the German POWs called die schlafende indianer (“the sleeping indians”). Bumbling about with paper maps and Ray’s notes, Dad and I scoured the neighborhoods in between these landmarks for any sign of the POW camp.

Most of the camp site was a collection of automobile dealerships called the Tempe Auto Park. Compound 4, where Drechsler met his end, was beneath the asphalt and landscaping of an Infiniti dealership. We did find some lingering cement artifacts from the camp, including some pylons which initially supported one of the guard towers. Some of the houses in the area appeared to have the same architecture as the camp buildings and may have been repurposed, and the old officer’s club was (and still is) the Tempe Elk’s Club. You can see some of the photos I took during our 1999 trip in the slideshow below.

Today, this area had changed again. Most of the autopark has been razed to make way for luxury apartments and although you can find some scattered remains and memorials, Papago Park POW Camp is nothing but a memory.

By January 1999, my father and I were deeply invested in Drechsler’s story and drove from Tucson to Tempe to find what remained of the Papago Park site. Half a century had elapsed, and most of the area was buried beneath modern construction. Fortunately, there were two prominent landmarks still in existence. The first was the Arizona Crosscut Canal which ran up the eastern perimeter of the POW camp. The second was Barnes Butte, a lumpy outcrop of granite to the west that the German POWs called die schlafende indianer (“the sleeping indians”). Bumbling about with paper maps and Ray’s notes, Dad and I scoured the neighborhoods in between these landmarks for any sign of the POW camp.

Most of the camp site was a collection of automobile dealerships called the Tempe Auto Park. Compound 4, where Drechsler met his end, was beneath the asphalt and landscaping of an Infiniti dealership. We did find some lingering cement artifacts from the camp, including some pylons which initially supported one of the guard towers. Some of the houses in the area appeared to have the same architecture as the camp buildings and may have been repurposed, and the old officer’s club was (and still is) the Tempe Elk’s Club. You can see some of the photos I took during our 1999 trip in the slideshow below.

Today, this area had changed again. Most of the autopark has been razed to make way for luxury apartments and although you can find some scattered remains and memorials, Papago Park POW Camp is nothing but a memory.

FROM FACT TO FICTION: MURDER, MYSTERY AND JUSTICE FROM BEYOND THE GRAVE

Dad and I never returned to the Papago Park site after our 1999 visit, but the memory of it and Werner Drechsler lingered in the back of my head for years.

For Ray, my father and myself, there was sympathy for Drechsler. Like so many other Germans who resisted the Nazi regime, Drechsler certainly knew the risks he was taking. Discovery would have meant death, but even if he had survived the war, he would have never been able to return to Germany. Although Drechsler’s murderers were subsequently tried and executed, it did little to acknowledge Drechsler's sacrifice.

As the years passed, I came back to Drechsler's story again and again, and eventually the plot for His Life Abiding began to manifest, Although my first inclination was to write the book as a ghost story, this didn't provide the character of the murdered POW with any chance for justice. So instead, it used reincarnation as a twist on themes typically found in ghost stories and murder mysteries. Using concepts from parapsychology — such as synchronicity (meaningful coincidences) and retrocognition (knowledge of a past event which could not have been learned or inferred by normal means) — meant the protagonists could unravel the book's central mystery without a wailing apparition showing them the way.

Ten years on, I'm very proud that His Life Abiding continues to find readers. Even more, I'm proud of what the book symbolized for me personally — the life-long desire to be a published author.

For those of you who have read His Life Abiding, thank you. For those of you who might be interested in doing so, you can find it through the usual online booksellers or contact your local bookstore or library. Reviews available on Goodreads.

For more information about Werner Drechsler, read Wittingham’s book or Death at Papago Park POW Camp: A Tragic Murder and America’s Last Mass Execution by Jane Eppinga.

Dad and I never returned to the Papago Park site after our 1999 visit, but the memory of it and Werner Drechsler lingered in the back of my head for years.

For Ray, my father and myself, there was sympathy for Drechsler. Like so many other Germans who resisted the Nazi regime, Drechsler certainly knew the risks he was taking. Discovery would have meant death, but even if he had survived the war, he would have never been able to return to Germany. Although Drechsler’s murderers were subsequently tried and executed, it did little to acknowledge Drechsler's sacrifice.

As the years passed, I came back to Drechsler's story again and again, and eventually the plot for His Life Abiding began to manifest, Although my first inclination was to write the book as a ghost story, this didn't provide the character of the murdered POW with any chance for justice. So instead, it used reincarnation as a twist on themes typically found in ghost stories and murder mysteries. Using concepts from parapsychology — such as synchronicity (meaningful coincidences) and retrocognition (knowledge of a past event which could not have been learned or inferred by normal means) — meant the protagonists could unravel the book's central mystery without a wailing apparition showing them the way.

Ten years on, I'm very proud that His Life Abiding continues to find readers. Even more, I'm proud of what the book symbolized for me personally — the life-long desire to be a published author.

For those of you who have read His Life Abiding, thank you. For those of you who might be interested in doing so, you can find it through the usual online booksellers or contact your local bookstore or library. Reviews available on Goodreads.

For more information about Werner Drechsler, read Wittingham’s book or Death at Papago Park POW Camp: A Tragic Murder and America’s Last Mass Execution by Jane Eppinga.