BACK TO POP CULTURE

December 24, 2022:

A chapter in my upcoming book, My Summer (and the Song of Cicadas), takes place in a video arcade. It has me recollecting on what was once a real institution of American childhood, especially if you grew up during the 1980s. Set in 1981, Cicadas will provide the reader with a peek into how arcades were during their infancy, just as video games were taking the world by storm. Those early games now read like a who’s who of arcade giants: Space Invaders (1978), Asteroids (1979), Pac-Man (1980), Donkey Kong, Galaga, Frogger and Defender (these last four all released in 1981). By today’s standards, the games were rudimentary and their graphics primitive, so it’s easy to forget they revolutionized our entire entertainment industry.

For many people, including my friends, arcade games were an addiction. Yet my interaction with arcades lasted only a decade or approximately 1982 to 1992. The first ones to pop up in my Tucson, Arizona neighborhood were makeshift businesses akin to the Spirit Halloween shops that briefly occupy an empty storefront and then slip quietly away in the middle of the night. If the storefront had enough floor space and electrical capacity to support those machines, you could have an arcade. It was undoubtedly easy money for the proprietors as little investment was needed beyond the game consoles and their occasional repair.

These early arcades were always dark. With their blacked-out windows and lights off, they were like casinos in that you had no awareness of the passage of time. They smelled a little like dirty carpet and a lot like body odor. They were incessantly loud, but you could always find the change machine by following the distinctive rattle of quarters as they sluiced into the metal dispenser. They were always crowded, yet they had their protocols to keep things orderly, such as placing a coin on the console if you wanted to be the next player of a particular machine. You could watch someone play, but it was impolite to comment or criticize — at least to their face.

December 24, 2022:

A chapter in my upcoming book, My Summer (and the Song of Cicadas), takes place in a video arcade. It has me recollecting on what was once a real institution of American childhood, especially if you grew up during the 1980s. Set in 1981, Cicadas will provide the reader with a peek into how arcades were during their infancy, just as video games were taking the world by storm. Those early games now read like a who’s who of arcade giants: Space Invaders (1978), Asteroids (1979), Pac-Man (1980), Donkey Kong, Galaga, Frogger and Defender (these last four all released in 1981). By today’s standards, the games were rudimentary and their graphics primitive, so it’s easy to forget they revolutionized our entire entertainment industry.

For many people, including my friends, arcade games were an addiction. Yet my interaction with arcades lasted only a decade or approximately 1982 to 1992. The first ones to pop up in my Tucson, Arizona neighborhood were makeshift businesses akin to the Spirit Halloween shops that briefly occupy an empty storefront and then slip quietly away in the middle of the night. If the storefront had enough floor space and electrical capacity to support those machines, you could have an arcade. It was undoubtedly easy money for the proprietors as little investment was needed beyond the game consoles and their occasional repair.

These early arcades were always dark. With their blacked-out windows and lights off, they were like casinos in that you had no awareness of the passage of time. They smelled a little like dirty carpet and a lot like body odor. They were incessantly loud, but you could always find the change machine by following the distinctive rattle of quarters as they sluiced into the metal dispenser. They were always crowded, yet they had their protocols to keep things orderly, such as placing a coin on the console if you wanted to be the next player of a particular machine. You could watch someone play, but it was impolite to comment or criticize — at least to their face.

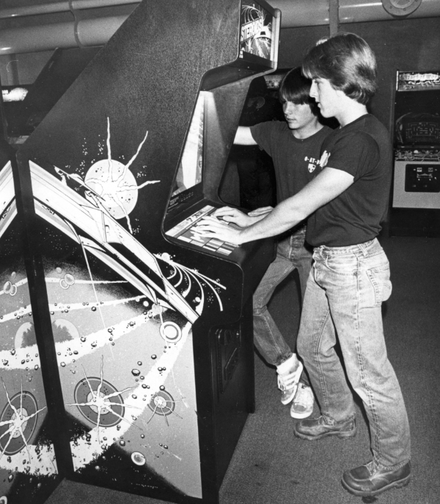

Two teens playing Asteroids in October 1981. Photo credit: Denver Public Library. Photo by Steve Groer.

Two teens playing Asteroids in October 1981. Photo credit: Denver Public Library. Photo by Steve Groer.

In high school, an arcade called Starbase 22 popped up about five minutes from campus. Unlike most arcades, the owners put more effort into their marketing strategy. Aside from the science fiction motif, there was a huge, homemade “wheel of fortune” you could spin to determine how many quarters you’d get back on your dollar. There was the possibility of getting double coins, but there was also the possibility of getting nothing. Still, it was a destination spot for my peers because it extended the high school experience for a few more hours and fed their addiction to obtain higher and higher scores. Yet, I don’t recall Starbase 22 surviving more than a few years. Like so many others, it fed a fad but was never intended to be a lasting business venture.

By the time I was in college, visiting arcades was an occasional activity at best. Sometimes I’d migrate to the small arcade in the University of Arizona’s Student Union. But when you’re in college, the value of money becomes obvious and I was more likely to use my precious spare change on gas or food. Additionally, a friend had an Atari home computer and text-based video games like the Zork series (1977-1982), which were early indicators that the arcade’s days were numbered.

By the 1990s, arcades were struggling. Some, like Wunderland on Tucson’s east side, lured in players by charging only a nickel per game. It worked but the message behind it was clear — no one was willing to pay a whole quarter for a video game anymore. Like most arcades, Wunderland occupied a building that originally had a different purpose… a shoe store, I think. My friend Phill and I went in the evenings after work, so I never actually saw the place in the daylight. We enjoyed Toobin’ (1988), a game where you paddled down treacherous rivers on an innertube, avoiding hazards and flinging empty beer cans at enemies. The game was older and unpopular, so we could play for hours without irritating anyone or depleting our cash.

By the time I was in college, visiting arcades was an occasional activity at best. Sometimes I’d migrate to the small arcade in the University of Arizona’s Student Union. But when you’re in college, the value of money becomes obvious and I was more likely to use my precious spare change on gas or food. Additionally, a friend had an Atari home computer and text-based video games like the Zork series (1977-1982), which were early indicators that the arcade’s days were numbered.

By the 1990s, arcades were struggling. Some, like Wunderland on Tucson’s east side, lured in players by charging only a nickel per game. It worked but the message behind it was clear — no one was willing to pay a whole quarter for a video game anymore. Like most arcades, Wunderland occupied a building that originally had a different purpose… a shoe store, I think. My friend Phill and I went in the evenings after work, so I never actually saw the place in the daylight. We enjoyed Toobin’ (1988), a game where you paddled down treacherous rivers on an innertube, avoiding hazards and flinging empty beer cans at enemies. The game was older and unpopular, so we could play for hours without irritating anyone or depleting our cash.

Young gamers in a Tucson arcade in 2004.

Young gamers in a Tucson arcade in 2004.

By the time the 21st century rolled around, arcades were increasingly attached to theme parks, miniature golf courses, and bowling alleys. They were something to be enjoyed in addition to other activities, but they were no longer the activity itself. When I worked as the Director of Education for the Humane Society in Tucson, we took our summer camp kids to a local theme park during the final day of their program. But if the children played in the video arcade, it was always to get the tickets the machines dispensed and trade them in for prizes. The prestige of having a high score, and putting in your initials on a game’s leaderboard, was no longer critical. Yet for more serious players, places like the Namco arcades could still be found in malls. Yet these were a far cry from their 1980s counterparts — corporate slickness bathed in neon where games cost a dollar or more to play.

Forty years on, I can still find arcades near my home in Oregon, and ironically they're very similar to what I knew in the 80s. Universally referred to as “retro arcades,” the name embraces its redundancy. Unlike the arcades of my youth, these places often serve food and alcohol because their demographic isn’t young players but Gen Xers and Millennials attracted by the thought of a nostalgic night out.

Does this mean there's hope for the arcade? Who knows. Maybe in some fashion or another, the arcade will always exist? But that first era in the 1980s when they were (ahem) game-changers will never return. That era, like a video game, was intense, exciting, and all too brief.

RELATED: Growing Up in Arcades: 1979-1989 on Flickr

Forty years on, I can still find arcades near my home in Oregon, and ironically they're very similar to what I knew in the 80s. Universally referred to as “retro arcades,” the name embraces its redundancy. Unlike the arcades of my youth, these places often serve food and alcohol because their demographic isn’t young players but Gen Xers and Millennials attracted by the thought of a nostalgic night out.

Does this mean there's hope for the arcade? Who knows. Maybe in some fashion or another, the arcade will always exist? But that first era in the 1980s when they were (ahem) game-changers will never return. That era, like a video game, was intense, exciting, and all too brief.

RELATED: Growing Up in Arcades: 1979-1989 on Flickr