<<BACK TO POP CULTURE

February 4, 2023:

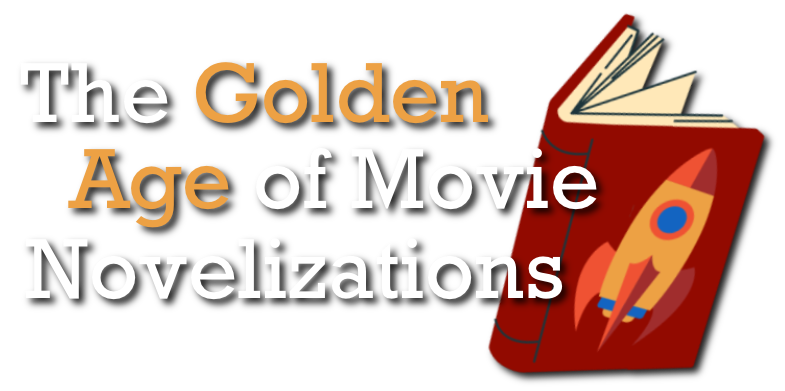

Today, there are movies based on books and books based on movies. And some books are literal adaptations of movie and television shows’ screenplays. These are called novelizations, and the 1970s and 80s, when home video and movie merchandising were still in their infancy, was their Golden Era. During those two decades, if you were a fan of a particular film or TV show and wanted more, the novelization was your first and sometimes the only option.

As a little nerd boy, I was on a constant quest to find novelizations, even though they were rarely good literature or even a decent read. Such was my hunger for fan merchandise that I was often hitting Waldenbooks or B. Dalton Books right after a movie’s final credits rolled. I treated the procured novelization like it was a holy tome. It went to school with me in my Trapper Keeper. The cover art became smudged and the pages dog-eared from all my reading and re-reading. Novelizations even inspired me to write my own fan lit — although it wasn’t called that at the time — and I may have been one of the first authors in history to pen a sequel to Star Wars. Of course, I was only ten at the time and my novelization never made it further than the pages of my Star Wars spiral notebook, but it underscores how this type of book could have an enduring impact on fans.

My interests ran toward science fiction and fantasy, and for these genres, novelizations generally fell into three major categories: the novel, the photo novel, and the comic book. In this blog however, it will just deal with the first of these. However, read My Most Forbidden Book for information about a famous photo novelization.

February 4, 2023:

Today, there are movies based on books and books based on movies. And some books are literal adaptations of movie and television shows’ screenplays. These are called novelizations, and the 1970s and 80s, when home video and movie merchandising were still in their infancy, was their Golden Era. During those two decades, if you were a fan of a particular film or TV show and wanted more, the novelization was your first and sometimes the only option.

As a little nerd boy, I was on a constant quest to find novelizations, even though they were rarely good literature or even a decent read. Such was my hunger for fan merchandise that I was often hitting Waldenbooks or B. Dalton Books right after a movie’s final credits rolled. I treated the procured novelization like it was a holy tome. It went to school with me in my Trapper Keeper. The cover art became smudged and the pages dog-eared from all my reading and re-reading. Novelizations even inspired me to write my own fan lit — although it wasn’t called that at the time — and I may have been one of the first authors in history to pen a sequel to Star Wars. Of course, I was only ten at the time and my novelization never made it further than the pages of my Star Wars spiral notebook, but it underscores how this type of book could have an enduring impact on fans.

My interests ran toward science fiction and fantasy, and for these genres, novelizations generally fell into three major categories: the novel, the photo novel, and the comic book. In this blog however, it will just deal with the first of these. However, read My Most Forbidden Book for information about a famous photo novelization.

Understanding the Novelization

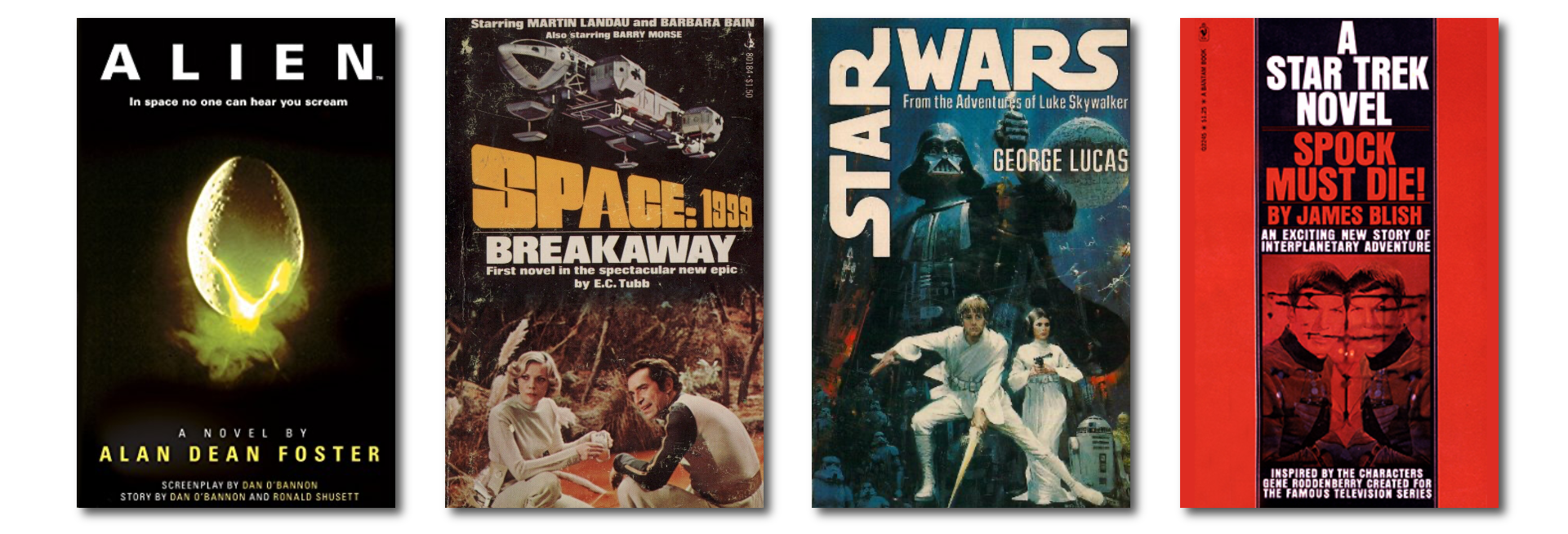

Novelizations were typically written by authors who could quickly produce a work of 125 to 200 pages based on the movie or TV show’s screenplay. The writers were rarely given the license to expand on the storyline or convey unauthorized nuance or detail. In many cases, to prevent spoilers, they might be asked to write the book without having seen the film or even given pertinent details. For example, if you read the novelization of Alien by Alan Dean Foster (1979), you’ll find little physical description of the creature itself. Twentieth Century Fox refused to tell Foster anything about the alien or even provide a photo, so in some respect, he wrote the book in a vacuum as dark and vast as space itself.

You can identify these gaps in information if you read carefully. In Breakaway, the first Space: 1999 novelization written by E.C. Tubb in 1975, the main character of Commander John Koenig was also given only a cursory physical description:

He made, she thought, a fine figure of a man. Not young, yet far from old, nearly trim in his uniform with the one black sleeve of command. His face was intense, sombrely handsome, the mouth sensitive, the eyes dark, enigmatic. A man of controlled passion and, she suspected, a lonely one.

Those are fifty-two words that say very little about a very important character. They certainly don’t describe Martin Landau, the famous actor who portrayed Koenig, and maybe Tubb wasn’t even aware that Landau had been cast in the role when he sat down to write the book.

Likewise, spacecraft, locations, equipment, and even interpersonal relationships were described only broadly. In some cases, the descriptions were baffling. When Tubb characterized the moonbase as “a garbage heap” (page 9), it was counterintuitive to the state-of-the-art scientific facility depicted in the show. And such anomalies could have a reader scratching their head in confusion.

Novelizations were typically written by authors who could quickly produce a work of 125 to 200 pages based on the movie or TV show’s screenplay. The writers were rarely given the license to expand on the storyline or convey unauthorized nuance or detail. In many cases, to prevent spoilers, they might be asked to write the book without having seen the film or even given pertinent details. For example, if you read the novelization of Alien by Alan Dean Foster (1979), you’ll find little physical description of the creature itself. Twentieth Century Fox refused to tell Foster anything about the alien or even provide a photo, so in some respect, he wrote the book in a vacuum as dark and vast as space itself.

You can identify these gaps in information if you read carefully. In Breakaway, the first Space: 1999 novelization written by E.C. Tubb in 1975, the main character of Commander John Koenig was also given only a cursory physical description:

He made, she thought, a fine figure of a man. Not young, yet far from old, nearly trim in his uniform with the one black sleeve of command. His face was intense, sombrely handsome, the mouth sensitive, the eyes dark, enigmatic. A man of controlled passion and, she suspected, a lonely one.

Those are fifty-two words that say very little about a very important character. They certainly don’t describe Martin Landau, the famous actor who portrayed Koenig, and maybe Tubb wasn’t even aware that Landau had been cast in the role when he sat down to write the book.

Likewise, spacecraft, locations, equipment, and even interpersonal relationships were described only broadly. In some cases, the descriptions were baffling. When Tubb characterized the moonbase as “a garbage heap” (page 9), it was counterintuitive to the state-of-the-art scientific facility depicted in the show. And such anomalies could have a reader scratching their head in confusion.

The Mold and Breaking the Mold

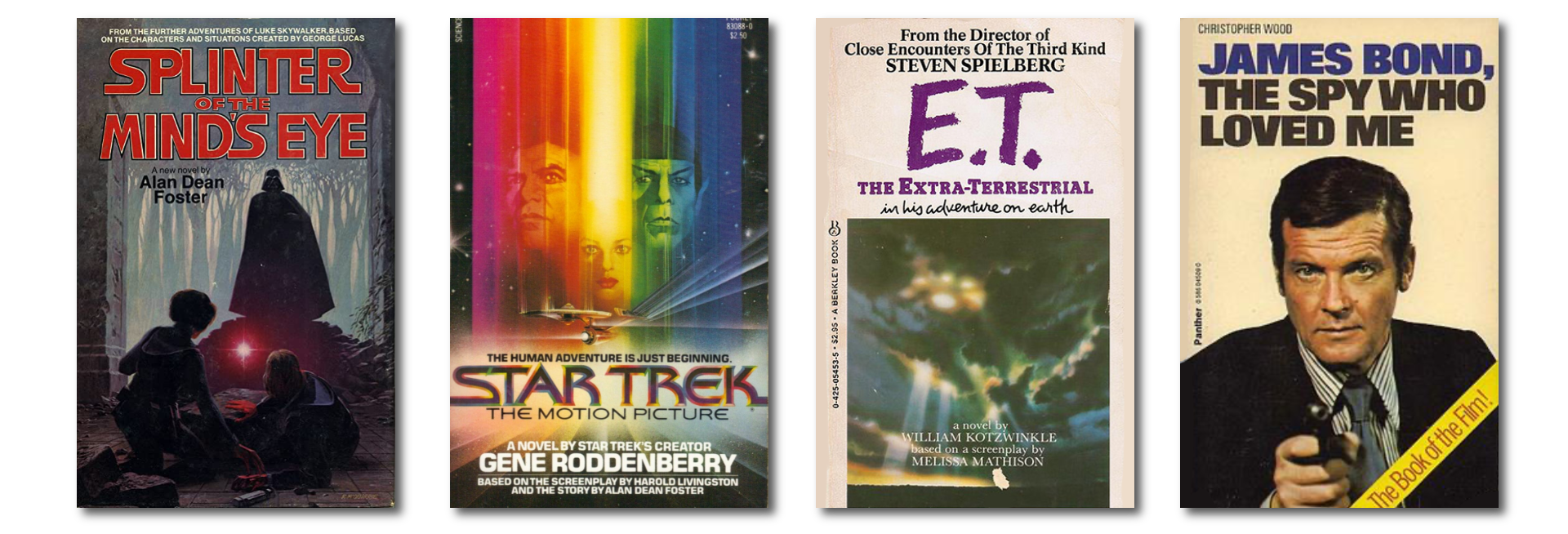

To be fair, writing novelizations had to be frustrating. Aside from having to work quickly with limited source material, authors often published anonymously as ghostwriters or under pseudonyms. (Tubb had fifty-two pen names alone!) A few years before he wrote Alien, Foster wrote one of the biggest-selling novelizations of all time — Star Wars (1977). The book was listed on New York Times Paperback Best Sellers list for nearly four months, but was solely credited to George Lucas. The following year, Foster released Splinter of the Mind’s Eye, the first original Star Wars novel which was published under his own name. Splinter is arguably the better book because Foster was allowed more creative freedom. It also popularized a sub-category of the novelization, the tie-in novel.

Foster wasn’t the first science fiction author who started with a novelization and ended up writing original tie-ins. Starting in 1967, Bantam Books began publishing a series of Star Trek novels based on original series episodes and penned by James Blish. Blish openly hated novelizations and tie-ins but later admitted that writing for Star Trek was a smart move professionally. He may have started out with little knowledge or enthusiasm for Star Trek, but in 1970 Blish produced one of the most highly-acclaimed original Trek novels of all time: Spock Must Die! Whether he foresaw that future or not, Blish became a Star Trek authority and his novelizations contributed heavily to its legacy and canon.

To be fair, writing novelizations had to be frustrating. Aside from having to work quickly with limited source material, authors often published anonymously as ghostwriters or under pseudonyms. (Tubb had fifty-two pen names alone!) A few years before he wrote Alien, Foster wrote one of the biggest-selling novelizations of all time — Star Wars (1977). The book was listed on New York Times Paperback Best Sellers list for nearly four months, but was solely credited to George Lucas. The following year, Foster released Splinter of the Mind’s Eye, the first original Star Wars novel which was published under his own name. Splinter is arguably the better book because Foster was allowed more creative freedom. It also popularized a sub-category of the novelization, the tie-in novel.

Foster wasn’t the first science fiction author who started with a novelization and ended up writing original tie-ins. Starting in 1967, Bantam Books began publishing a series of Star Trek novels based on original series episodes and penned by James Blish. Blish openly hated novelizations and tie-ins but later admitted that writing for Star Trek was a smart move professionally. He may have started out with little knowledge or enthusiasm for Star Trek, but in 1970 Blish produced one of the most highly-acclaimed original Trek novels of all time: Spock Must Die! Whether he foresaw that future or not, Blish became a Star Trek authority and his novelizations contributed heavily to its legacy and canon.

They’re Not ALL Bad

Despite their not-undeserved reputations as poorly written exercises in commercialism, even in the 1970s and 80s there were plenty novelizations worth reading.

In 1982, William Kotzwinkle penned the adaptation for E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, co-credited with screenwriter Melissa Mathison. Like Star Wars, Kotzwinkle’s book spent a lot of time on the best seller’s list, and not just because it was tied to one of the biggest science fiction films of the decade. Told with humor and insight, E.T. did more than just imitate its source material, it expanded and enhanced it. An experienced writer for youth and children, Kotzwinkle was well suited to adapt a movie mainly about pre-teens and teens to book form, and to this day, the novel is hailed as an exceptional piece of young adult literature. Consider this passage:

Mary sighed, folding her paper. Goblins, mercenaries, orks, you name it, she had it, down in her kitchen, night after night, as well as the rubble of a ruined city of Crush bottles, potato-chip bags, books, papers, calculators, and horrible oaths pinned to her memo board. If anyone knew in advance what it was to raise kids, they would never do it.

Now the group broke into song:

"She was 12 when he yanked the plug.

15 reds and a jug of wine…"

What a lovely song, thought Mary, her teeth gnashing at the thought of one of her own babies taking a handful of reds some night, or a handful of something else, LSD, DMT, XYZ, who knew what they would come up with next? And ork, maybe?

Goodreads has an interesting list entitled “The Novelization Was Better Than the Movie” which details some reader picks which, like Kotzwinkle's book, exceeded their source material. Of those written during the 1970s and 80s, I can attest that the novelizations for Star Trek: The Motion Picture and James Bond: The Spy Who Loved Me certainly surpassed their big-screen counterparts.

Despite their not-undeserved reputations as poorly written exercises in commercialism, even in the 1970s and 80s there were plenty novelizations worth reading.

In 1982, William Kotzwinkle penned the adaptation for E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial, co-credited with screenwriter Melissa Mathison. Like Star Wars, Kotzwinkle’s book spent a lot of time on the best seller’s list, and not just because it was tied to one of the biggest science fiction films of the decade. Told with humor and insight, E.T. did more than just imitate its source material, it expanded and enhanced it. An experienced writer for youth and children, Kotzwinkle was well suited to adapt a movie mainly about pre-teens and teens to book form, and to this day, the novel is hailed as an exceptional piece of young adult literature. Consider this passage:

Mary sighed, folding her paper. Goblins, mercenaries, orks, you name it, she had it, down in her kitchen, night after night, as well as the rubble of a ruined city of Crush bottles, potato-chip bags, books, papers, calculators, and horrible oaths pinned to her memo board. If anyone knew in advance what it was to raise kids, they would never do it.

Now the group broke into song:

"She was 12 when he yanked the plug.

15 reds and a jug of wine…"

What a lovely song, thought Mary, her teeth gnashing at the thought of one of her own babies taking a handful of reds some night, or a handful of something else, LSD, DMT, XYZ, who knew what they would come up with next? And ork, maybe?

Goodreads has an interesting list entitled “The Novelization Was Better Than the Movie” which details some reader picks which, like Kotzwinkle's book, exceeded their source material. Of those written during the 1970s and 80s, I can attest that the novelizations for Star Trek: The Motion Picture and James Bond: The Spy Who Loved Me certainly surpassed their big-screen counterparts.

Novelizations Today

While novelizations are still widely published, they no longer occupy the important merchandising space they once had forty or fifty years ago. They might also become lost in the jungle of other books that are invariably published about movie and television franchises, including nonfiction titles dealing with everything from production design to concept art. In a sense, the novelizations is a bit of a lost art form — if it was an art form at all.

Perhaps the more realistic and important role novelizations played was what they represented to the fans in the 70s and 80s, before fandom was widely embraced. They were the chance to extend the fantasy of the movie-going experience a little further, relive it at home in your own time, and imagine how other stories set in those worlds would play out…

I still own dozens of novelizations of movies and TV shows from the 1970s and 80s with their smudged covered and yellowing pages. I doubt I will ever reread them because most are awful. But their sentimental value has never faded.

While novelizations are still widely published, they no longer occupy the important merchandising space they once had forty or fifty years ago. They might also become lost in the jungle of other books that are invariably published about movie and television franchises, including nonfiction titles dealing with everything from production design to concept art. In a sense, the novelizations is a bit of a lost art form — if it was an art form at all.

Perhaps the more realistic and important role novelizations played was what they represented to the fans in the 70s and 80s, before fandom was widely embraced. They were the chance to extend the fantasy of the movie-going experience a little further, relive it at home in your own time, and imagine how other stories set in those worlds would play out…

I still own dozens of novelizations of movies and TV shows from the 1970s and 80s with their smudged covered and yellowing pages. I doubt I will ever reread them because most are awful. But their sentimental value has never faded.