BACK TO STORYTELLING

June 11, 2020:

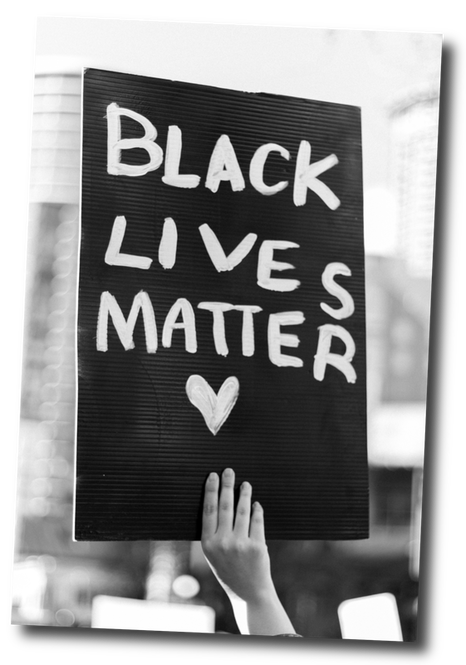

Like so many of us, I've been watching what's been happening around the world and on the streets of my own community with a mixture of shock, fear, grief and hope. Already faced with the awesome challenges of climate change and a global pandemic, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of four Minneapolis Police officers has ignited an entire movement frustrated by what they see as a dual system where only a few Americans enjoy the privileges and protections promised to all. One thing many people have noted is how younger Americans of all backgrounds are engaged in the current civil disobedience.

So has something changed? Why have the younger generations, often considered apathetic toward politics, suddenly become so political?

Maybe it's because when you're talking to young people about inequality (for LBGTQ+ people, people of color, women, the poor, whomever), you're not talking about abstracts. You're not talking about people younger Americans have never met or have no real information about. Instead, you're talking about their classmates, their best friends, their siblings, their parents, their heroes and their role models. In a lot of cases — maybe even most cases — you're also talking about them!

My late father, who grew up during the 1930s and 40s, inadvertently illustrated this for me years ago. Dad used to tell me stories about how the "colored kids" (yes, he still used that term, as much as my sister and I tried to break him of the habit) lived in an entirely different part of Battle Creek, Michigan, from himself. He was friendly with black kids at school, but at the end of the day, they went to a place he never saw, would never visit, and probably never thought about. Like gays of that era, blacks lived lives that were mostly, if not completely invisible, to white, middle class people like my father.

For many in my father's generation, this ugly paradigm worked. These "other people" could exist as long as they stayed in their places or stayed invisible. But as American society and the ways we communicate with each other has become more diverse, those invisible lives became visible. With visibility came familiarity. With familiarity came acceptance. With acceptance came compassion. And maybe that's why the current protests have been so large, so sustained, and so diverse.

June 11, 2020:

Like so many of us, I've been watching what's been happening around the world and on the streets of my own community with a mixture of shock, fear, grief and hope. Already faced with the awesome challenges of climate change and a global pandemic, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of four Minneapolis Police officers has ignited an entire movement frustrated by what they see as a dual system where only a few Americans enjoy the privileges and protections promised to all. One thing many people have noted is how younger Americans of all backgrounds are engaged in the current civil disobedience.

So has something changed? Why have the younger generations, often considered apathetic toward politics, suddenly become so political?

Maybe it's because when you're talking to young people about inequality (for LBGTQ+ people, people of color, women, the poor, whomever), you're not talking about abstracts. You're not talking about people younger Americans have never met or have no real information about. Instead, you're talking about their classmates, their best friends, their siblings, their parents, their heroes and their role models. In a lot of cases — maybe even most cases — you're also talking about them!

My late father, who grew up during the 1930s and 40s, inadvertently illustrated this for me years ago. Dad used to tell me stories about how the "colored kids" (yes, he still used that term, as much as my sister and I tried to break him of the habit) lived in an entirely different part of Battle Creek, Michigan, from himself. He was friendly with black kids at school, but at the end of the day, they went to a place he never saw, would never visit, and probably never thought about. Like gays of that era, blacks lived lives that were mostly, if not completely invisible, to white, middle class people like my father.

For many in my father's generation, this ugly paradigm worked. These "other people" could exist as long as they stayed in their places or stayed invisible. But as American society and the ways we communicate with each other has become more diverse, those invisible lives became visible. With visibility came familiarity. With familiarity came acceptance. With acceptance came compassion. And maybe that's why the current protests have been so large, so sustained, and so diverse.

"I'm more hopeful today than ever..." said Rev. Al Sharpton during his eulogy of George Floyd on June 4, 2020. "There is a time and a season. And when I looked this time, and saw the marchers where in some cases young whites outnumbered the blacks marching, I know that it's a different time and a different season. When I looked and saw people in Germany marching for George Floyd, it's a different time and a different season. When they went in front of the Parliament in London, England, and said it's a different time and a different season, I come to tell you, America, this is the time to be building accountability in the criminal justice system."

Curious about the diverse demographics of the protests, I asked some of my young, white friends (ages 13 to 31), why they thought so many whites are invested in what were once dismissed as "black issues", or "gay issues", or "women's issues..."

Their responses weren't just about fairness for all Americans, but about the institutions they see has holding the old paradigm in place — in particular, the police.

While I wasn't raised in a law-and-order mindset like the generations that preceded my own, I've always had a healthy respect for the police and even worked in the criminal justice system for over a decade. I've never felt targeted by police officers, but I acknowledge that this might be because I'm white, male and middle-class. That long established paradigm my father talked about when he was growing up still protects people like me from certain excesses and abuses. Yet this protection from ugly realities doesn't necessarily carry over to generations younger than my own. Or at least, they don't seem to think it does.

My friend Chris, age 31, is a real estate agent working in San Diego. He's successful and educated, and not somebody you would necessarily think is nervous about police brutality. Yet he told me this: "I think there's a genuine fear of police even from [younger] white people and the realization of what someone with that power can do left unchecked. In that regard, I question whether I'm any safer than a black person if I upset the wrong cop or catch him on a bad day... Chris Rock has a whole skit about how police say there're lower levels of socio-psychopaths and corruption within police than any other occupation... but again, it's like an airline saying they have pilots that only crash sometimes. In some occupations, there's just no room for error..."

Another friend, also named Chris (age 27), is a Master's student. He echoed those sentiments: "It's not like the system and the police system is just tilted against minorities. We are the first generation where tons of us actually think we can't afford kids or a house. The current paradigm is titled strongly towards 'the haves' to the point that my generation (Millennials) can't even find jobs that aren't minimum wage. I think my generation is more a part of the 'have nots,' so there's a lot in it for them to disrupt the paradigm, on top of generally being more accepting and liberal."

"Everyone, I feel, is tired of having overly armed, overly aggressive, and overly ambitious police overstep their purpose as public servants; and have stepped into a pseudo-militaristic role treating citizens like infidels," my youngest son, Myles (26), told me. "This movement has also brought on an alarming awareness that this isn't new. It's pervasiveness has only come to light because of smart phones and social media. I think [generations] become more tolerant of differences as ties to the old racial class system die, literally the generation of people who counter-protested Martin Luther King, Jr."

Some of the younger women I spoke to also addressed these generational differences and how old prejudices stubbornly cling to life. "I think young women look at how they are still getting paid so much less than men for the same work and they wonder how is this possible? Our mothers were upset with this decades ago but it's still here. It's like the same battles are being fought over and over again but never won. People on the other side just tell you it's not really a problem, or they gaslight you about it, in the hopes you'll just shut up."

Another young woman, age 18, drew a comparison between how blacks and women may be similarly mistreated by authority figures. "Blacks get harassed by the police and women get harassed by their bosses... or sometimes, just walking down the street. I think the Black Lives Matter movement and the Me Too movement and gay rights are all part of a bigger picture. It's about young people no longer turning a blind eye to this stuff."

The political polarization in America may have, in many ways, compelled younger people to take a stand as they've lost patience with the way the country (maybe the world?) is being managed.

"I believe now there is such a polarization in views unlike before, where you're either explicitly racist and ascribe to the antiquated values of American, or you come out and show some sign of support to the neo-progressive ideals of our generation," said Jake, age 21. "On the white side, it's a show of solidarity with fellow black citizens and wiping the old trend of racism off the charts. That's the ideal view, at least."

Even young teens, like Aleksa and Liam, both 13, are seeing the world as an inherently unfair place.

"Older generations grew up with the inequity being normal and they're tired of the fight," Aleksa said, explaining her view on the large number of young whites at the protests. "Also, it's safer for white people to protest than people of color, so they're out there trying to help."

Her brother, Liam, credited social media for helping to raise awareness and motivate people his age to join the struggle. "White people are showing up more because they're finally more aware of what people of color have always known," he told me.

Some young whites may want to be allies to others — but even more feel this fight is their fight, too. In many ways, they seem to be more in touch with that "equality for all" ideal that America was founded on and which is often claimed, but not necessarily practiced, by older generations.

For our youth, it really is a matter of what kind of world they'll inherit. So will they be able to change that world for the better? I don't know, but they seem anxious to try.

Curious about the diverse demographics of the protests, I asked some of my young, white friends (ages 13 to 31), why they thought so many whites are invested in what were once dismissed as "black issues", or "gay issues", or "women's issues..."

Their responses weren't just about fairness for all Americans, but about the institutions they see has holding the old paradigm in place — in particular, the police.

While I wasn't raised in a law-and-order mindset like the generations that preceded my own, I've always had a healthy respect for the police and even worked in the criminal justice system for over a decade. I've never felt targeted by police officers, but I acknowledge that this might be because I'm white, male and middle-class. That long established paradigm my father talked about when he was growing up still protects people like me from certain excesses and abuses. Yet this protection from ugly realities doesn't necessarily carry over to generations younger than my own. Or at least, they don't seem to think it does.

My friend Chris, age 31, is a real estate agent working in San Diego. He's successful and educated, and not somebody you would necessarily think is nervous about police brutality. Yet he told me this: "I think there's a genuine fear of police even from [younger] white people and the realization of what someone with that power can do left unchecked. In that regard, I question whether I'm any safer than a black person if I upset the wrong cop or catch him on a bad day... Chris Rock has a whole skit about how police say there're lower levels of socio-psychopaths and corruption within police than any other occupation... but again, it's like an airline saying they have pilots that only crash sometimes. In some occupations, there's just no room for error..."

Another friend, also named Chris (age 27), is a Master's student. He echoed those sentiments: "It's not like the system and the police system is just tilted against minorities. We are the first generation where tons of us actually think we can't afford kids or a house. The current paradigm is titled strongly towards 'the haves' to the point that my generation (Millennials) can't even find jobs that aren't minimum wage. I think my generation is more a part of the 'have nots,' so there's a lot in it for them to disrupt the paradigm, on top of generally being more accepting and liberal."

"Everyone, I feel, is tired of having overly armed, overly aggressive, and overly ambitious police overstep their purpose as public servants; and have stepped into a pseudo-militaristic role treating citizens like infidels," my youngest son, Myles (26), told me. "This movement has also brought on an alarming awareness that this isn't new. It's pervasiveness has only come to light because of smart phones and social media. I think [generations] become more tolerant of differences as ties to the old racial class system die, literally the generation of people who counter-protested Martin Luther King, Jr."

Some of the younger women I spoke to also addressed these generational differences and how old prejudices stubbornly cling to life. "I think young women look at how they are still getting paid so much less than men for the same work and they wonder how is this possible? Our mothers were upset with this decades ago but it's still here. It's like the same battles are being fought over and over again but never won. People on the other side just tell you it's not really a problem, or they gaslight you about it, in the hopes you'll just shut up."

Another young woman, age 18, drew a comparison between how blacks and women may be similarly mistreated by authority figures. "Blacks get harassed by the police and women get harassed by their bosses... or sometimes, just walking down the street. I think the Black Lives Matter movement and the Me Too movement and gay rights are all part of a bigger picture. It's about young people no longer turning a blind eye to this stuff."

The political polarization in America may have, in many ways, compelled younger people to take a stand as they've lost patience with the way the country (maybe the world?) is being managed.

"I believe now there is such a polarization in views unlike before, where you're either explicitly racist and ascribe to the antiquated values of American, or you come out and show some sign of support to the neo-progressive ideals of our generation," said Jake, age 21. "On the white side, it's a show of solidarity with fellow black citizens and wiping the old trend of racism off the charts. That's the ideal view, at least."

Even young teens, like Aleksa and Liam, both 13, are seeing the world as an inherently unfair place.

"Older generations grew up with the inequity being normal and they're tired of the fight," Aleksa said, explaining her view on the large number of young whites at the protests. "Also, it's safer for white people to protest than people of color, so they're out there trying to help."

Her brother, Liam, credited social media for helping to raise awareness and motivate people his age to join the struggle. "White people are showing up more because they're finally more aware of what people of color have always known," he told me.

Some young whites may want to be allies to others — but even more feel this fight is their fight, too. In many ways, they seem to be more in touch with that "equality for all" ideal that America was founded on and which is often claimed, but not necessarily practiced, by older generations.

For our youth, it really is a matter of what kind of world they'll inherit. So will they be able to change that world for the better? I don't know, but they seem anxious to try.

My upcoming novel My Summer (and the Song of Cicadas) features a video arcade in one chapter. Writing about it made me reconsider the role arcades played in my life, starting in the early 1980s.